-

27 Aug 2024

27 Aug 2024Supporting life-saving cancer research

-

27 Apr 2024

27 Apr 2024Innovation through research

-

27 Jul 2022

27 Jul 2022Supporting future clinicians

-

27 Nov 2021

27 Nov 2021Personalising medicine for blood cancer patients

-

21 Sept 2021

21 Sept 2021New partnership to scale up CAR T-cell cancer treatment in New Zealand

-

31 Mar 2021

31 Mar 2021Bringing cutting-edge treatment to Kiwis – a Vision to Cure

-

27 Aug 2020

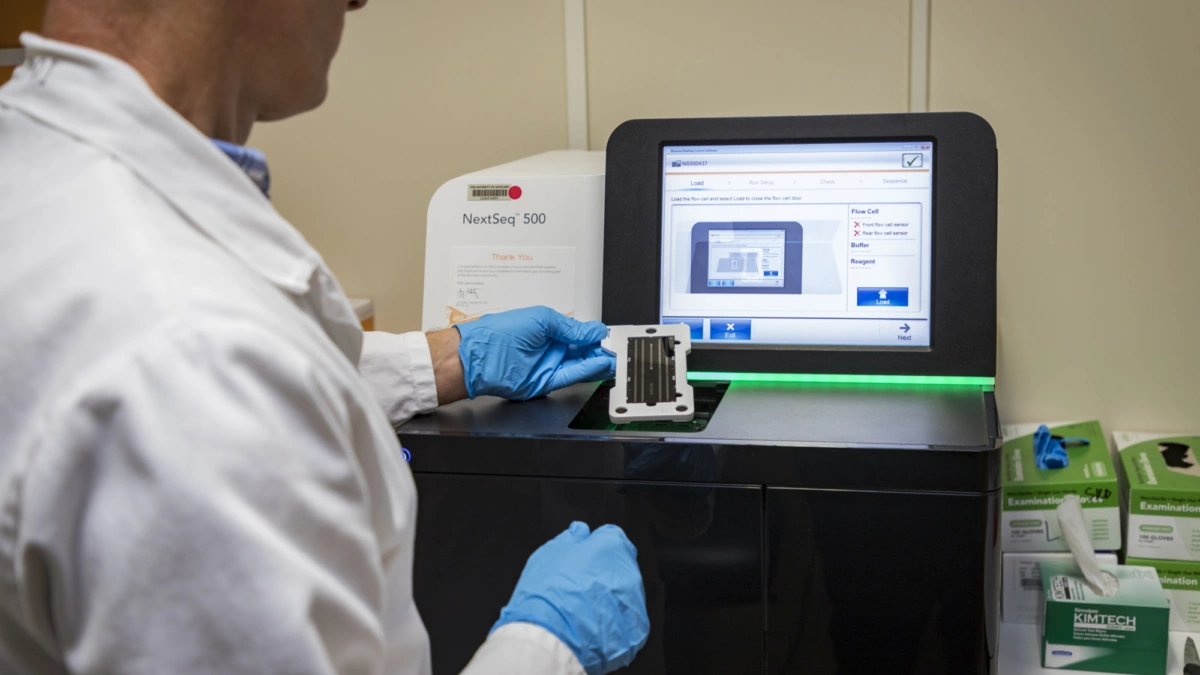

27 Aug 2020Gene sequencing – a Vision to Cure

-

27 Jul 2019

27 Jul 2019UK’s drug-buying agency CEO: Why we like to say ‘yes’

-

27 Jun 2019

27 Jun 2019Cancer Patients Miracle Means $540,000 Treatment Is Free

-

07 Jun 2019

07 Jun 2019Do You Know About Haemochromatosis?